Isaiah 40:3-5 (New Living Translation)

“3Listen! I hear the voice of someone shouting, “Make a highway for the LORD through the wilderness. Make a straight, smooth road through the desert for our God. 4Fill the valleys and level the hills. Straighten out the curves and smooth off the rough spots. 5Then the glory of the LORD will be revealed, and all people will see it together. The LORD has spoken!”

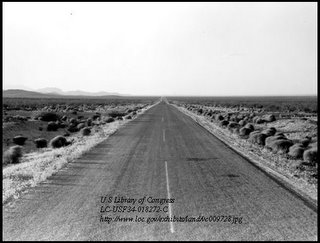

This morning I was giving thought to a long trip home I took in 1966, particularly a long part of the journey through the desert landscape of America’s southwest. Starting at Travis Air Force Base, I tagged along with a group of three other guys in a beat up old Ford. I was on my way to Boston, another was on his way to Oklahoma City, another to Dayton, Ohio, and Hollis Oliver, whom we called “Moses,” was on his way to Atlanta, Georgia. For three days we passed through the heat of Death Valley, dropped a muffler somewhere in Arizona, and made our way to high ground during a flash flood between Tucumcari, New Mexico and Amarillo, Texas. I split up with the group in Oklahoma City and made my way to Boston in increments, thanks to the generosity of a series of long-haul truckers.

I didn't make it home by chance. I made it to Boston because I knew where I was coming from and also knew where I wanted to go. One of the great lessons I learned on that trip was the value of a road map, of knowing where I’ve been and where I’m going in life.

I suspect this all puts me at odds with the flow of the culture I live in. While I’m no expert on the subject, I’m told I live in a post-modern world, where roadmaps are often considered an unnecessary burden for the traveler.

In 1994, Presbyterian theologian Daniel Adams described some of the dominant post-modern themes in the following manner:

“At least four major themes can be discerned in postmodernism.(29) The first is a rejection of classical metaphysical thought. This is, in a sense, a rejection of a philosophical metanarrative that formed the foundation for much of Western thought. The nature of reality is not found in objective truth but in the phenomenological linguistic event. Metaphysical objectivity is replaced by sociological subjectivity. In theology this rejection of classical metaphysics has taken the form of a shift from deductive theology to inductive theology.(30) This shift lies at the foundation of liberation theology and the numerous socio-political theologies now in vogue.”

“This sociological subjectivity leads to the second major theme which is a rejection of human autonomy. The subject, that is, the person, is always part of a larger sociological matrix which includes history, culture, economics, religion, politics, and philosophical worldview. Theology does not “fall from the skies” but is constructed within a complex socio-cultural matrix.(31)”

“These first two themes have led to a movement in contemporary theology known as nonfoundationalism,(32) which seeks to disassociate theology from objective foundations such as Scripture, creeds and confessions, and ecclesiastical tradition. Theology, in this framework, arises out of the needs of the community within the ever-changing contexts of culture and history. Scripture, creeds and confessions, and ecclesiastical tradition are part of the ever-changing contexts of culture and history and cannot, therefore, serve as the foundations for theological life and work. Ethics rather than doctrine is central to the task of theological construction; hence doctrine emerges from ethics rather than ethics from doctrine as in traditional theology.”

“A third theme in postmodernism is praxis, that is, serious concern for the practical ethical aspects of human life. Postmodern thinkers have been especially harsh critics of the "underside" of modernism whereby people of non-Western cultures have been exploited, and oppressed. This is why the contextual theologies from the non-Western world, as well as feminist, womanist, African-American, Hispanic, and other theologies from marginalized groups, place so much emphasis upon praxis. Theology is not only to be thought; it is also to be lived. Whereas philosophy has traditionally been the dialogue partner with theology, today it is sociology. Orthopraxis replaces orthodoxy.”

“The fourth major theme is a strong anti-Enlightenment stance. Some postmodernists even call the West's attempts to make its values universal intellectual terrorism.(33) Taken together, praxis and a strong anti-Enlightenment stance involve a rejection of the West, an attractive perspective for Islamic scholars.(34) There is in postmodern theology a decided turning away from the Enlightenment tradition with concurrent attempts to recover the insights of traditional cultures.”

“The result is a pluralism of theologies with no one perspective assuming a dominant position in the church. Theologically speaking, we live in an intellectual marketplace which includes not only postmodern theologies, but also those that are both premodern and modern in their basic assumptions.”

If I read this correctly it says that post-modern theological thought is a process in which the pilgrim finds his or her way through the wilderness using the signs of the times or some internal spiritual barometer as guides. It’s a way of traveling the road of life by feel and instinct.

There are times when this seems very appealing to me. Years ago I answered the question Nancy raised of where I’d been in life and where I was going this way – “Where have I been? Back there! Where am I going? Out there!” In a fit of cleverness I called it my John Wayne theology. I didn’t need a roadmap to know where I’d been. I was right here, in the now. Nor did I need a roadmap to figure out where I was going. I was going “out there.” It was all that simple.

With the coming of age and maturity, though, I’ve changed. I like roadmaps. When I’m traveling from Emporia to Chicago or Santa Fe I take a roadmap with me so that I don’t get lost along the way. The same holds true of my theology. My journey in life is more than just a matter of wandering aimlessly through the wilderness. It began here on earth, in Boston, Massachusetts and it’s going to end in heaven. I wasn’t created to wander aimlessly, hoping that in the end I’d fumble my way into heaven.

Theologian C.S. Lewis once had an encounter with a man who was listening to one of his lectures about roadmaps and theology. “I’ve no use for all that stuff,” the man said. “But, mind you, I’m a religious man too. I know there’s a God. I’ve felt Him: out alone in the desert at night: the tremendous mystery. And that’s just why I don’t believe all your neat little dogmas and formulas about Him. To anyone who’s met the real thing they all seem so petty and pedantic and unreal!”

Lewis, the great defender of orthodoxy, had this to say in response:

“Now, Theology is like the map. Merely learning and thinking about the Christian doctrines, if you stop there, is less real and less exciting than the sort of thing my friend got in the desert. Doctrines are not God: they are only a kind of map. But the map is based on the experience of hundreds of people who really were in touch with God – experiences compared with which any thrills or pious feelings you and I are likely get on your own are very elementary and very confused. And, secondly, if you want to get any further, you must use the map. You see, what happened to that man in the desert may have been real, and was certainly exciting, but nothing comes of it. It leads nowhere. There is nothing to do about it. In fact, that is why a vague religion – all about feeling God in nature, and so on – is so attractive. It is all thrills and no work: like watching the waves from the beach. But you will not get to Newfoundland by studying the Atlantic that way, and you will not get eternal life by simply feeling the presence of God in flowers or music. Neither will you get anywhere by looking at maps without going to sea. Nor will you be very safe if you go to sea without a map.”

I’m with C.S. Lewis. I like the Christian roadmap, and I like the fact that it’s been tested over the centuries and has been found to be reliable. I’m wise enough now to know that without it, left to my own devices, I could easily get lost.

A man much wiser than I had something to say about subjective paths and aimless theological wandering. His words, like Lewis’s, are like anchors to me:

Proverbs 16:25 (King James Version)

“There is a way that seemeth right unto a man, but the end thereof are the ways of death.”

Another man, equally wise, had this to say about the subject:

2 Peter 1:16 (New Living Translation)

“For we were not making up clever stories when we told you about the power of our Lord Jesus Christ and his coming again. We have seen his majestic splendor with our own eyes.”

At a time when subjectivity is in and history and tradition are out I intend to stay out of step with the trends of the times. I’ve wandered before in the theological wilderness, fumbling around in the minefields of subjective truth. They’re poor substitutes for the real roadmap. I’ve learned over the years that all roads don’t lead to Rome, nor do all philosophies lead to the Celestial City. There is only One Way and it’s been proven trustworthy.

2 comments:

Wonderfully helpful post! Thanks.

Love it Phil! Very edifying!

Post a Comment