As with the previous post, this one will make much more sense if you read part one (if you haven’t read it already) and part two.

After the accident near Corner Brook I decided to maintain a low profile. My worldview and my ego were battered and needed a rest. I did maintain my love of the stout, though, and it was that love that was to really get me in trouble.

Alcohol can do amazing things. It can lower inhibitions. It can turn a normal human body into a poor imitation of a flopping fish. And it can cause a normally sensible person to let down their guard.

That was my problem. About a month or so after the accident I struck up a friendship with a guy from my unit who I’ll just refer to by his first name, Steve. Steve had been assigned to Ernest Harmon about a year after me, which meant that he was going to be there, I assumed, a year after I was gone. I met him at the airman’s club one night and we struck up a conversation over a couple of beers. One thing led to another over the next couple of weeks until Steve decided to “open up.” It was on one of our almost nightly tours of duty at the airman’s club he confided in me that he wanted to get his wife up to Newfoundland but didn’t have enough money for a down payment on a trailer house he had looked at and decided would be good for him and his wife. I didn’t pay much attention at first, but after three or four drinks I let my guard down. “How much money do you need? I asked. He looked pleadingly as he answered, “About two thousand.”

“That’s some serious money and I don’t have that kind of cash. Have you tried to get a loan?”

He slumped down in his chair. “Yeah, I tried, but they told me I would need a co-signer.”

“Well,” I slurred, “Why dontcha’ just go get one. It couldn’t be that hard.”

Steve grinned back. “How about you? You’d do that for a friend, wouldn’t you?”

“I can’t man.”

“Come on, man, you know I’m good for it. I’d never leave you high and dry.”

“I really can’t.”

“Please, Phil, please. I’m really desperate to see the old woman.”

If I’d been sober that night my life would have been so different. But I wasn’t. I foolishly agreed to co-sign a loan and a couple of weeks later Steve had the cash he needed.

After he got the cash Steve seemed to be less of a friend than he had before. He didn’t come by the airman’s club and any time I saw him while we were on duty he found a way to avoid me. I did corner him once and asked if his wife had gotten to Newfoundland. “Oh yeah," he assured me. “Things couldn’t be better.”

Something didn’t seem right. Have you ever had that internal railroad crossing go off inside you?” That’s what was happening to me. Any time I’d get around Steve after co-signing the loan that signal would go off. “Ding ding ding ding ding ding ding. Train coming. Don’t cross the tracks.”

I found out shortly after these brief encounters that I was in the middle of the tracks and a train was bearing down on me.

I got to my duty station one night and went to look for Steve to let him know I had some misgivings about having co-signed the loan. When I couldn’t find him I checked with one of the duty section’s NCOs. Where’s Steve?” I asked

“He got an emergency reassignment stateside.”

“You can’t be serious. What about his wife?”

“He ain’t married.”

“Yeah he is. He got me to co-sign a loan so that he could get her up here.”

“Well, if you ain’t the stupidest airman at Ernest Harmon. You’ve been conned.”

“I’m tellin’ you sarge, he’s married. He got the money to get her up here.”

“If you really believe that you’re even stupider than the stupidest airman at Ernest Harmon.”

It wasn’t long till the train hit me broadside. I got a letter, then a call from the finance company. They wanted their money. I told them to get it from Steve, but they told me that they were going to get it from me. I pleaded poverty. “I don’t have two thousand dollars.” That didn’t work either. The relationship with the finance company spiraled downward. They decided the loan was in default and they wanted all their money, immediately. Worse yet, they threatened to get the Air Force involved if I didn’t pay in full.

Now two thousand dollars may not seem like much these days, but back in 1964 it was a lot. I didn’t have the money. My mother didn’t have the money. No one I knew had the money. In desperation I checked my options within the military. There was one. I had to re-enlist, which I hadn’t planned on doing. But I was so desperate that I was willing to do anything. I signed over another four years of my life and got the two thousand dollars I needed.

Toward the end of my eighteen month tour someone showed me a picture he had found in a magazine of a Montagnard tribesman. It looked to me like the pictures I had seen in geography classes when I was in school or like something out of National Geographic. “Where’s this guy live?” I asked out of curiosity.

“Vietnam.”

“You mean Indo-China?”

“No, Vietnam.”

“We’ve got advisors over there, don’t we.”

“More than advisors. They’re lookin’ for volunteers.”

I didn’t know then what possessed me to do it, but as soon as I was finished with that conversation I went over to the orderly room and volunteered to go to Vietnam. Within a week I had shipping orders to report to the 1964th Communications Squadron at Tan son Nhut AFB, Vietnam.

A couple of months later found me on a Continental Airlines flight from Travis AFB to Saigon. I’ll never forget our approach into the airport. The flight crew played the 1944 tune “I’ll Be Seeing You”, then wished us well. As I looked out the window I thought it was ironic that someone like me would be serenaded with words like:

I'll be seeing you in all the old familiar places

That this heart of mine embraces all day through

In that small café, the park across the way

The children's carousel, the chestnut trees, the wishing well

I'll be seeing you in every lovely summer's day

In everything that's light and gay

I'll always think of you that way

I'll find you in the mornin' sunAnd when the night is new

I'll be looking at the moon

But I'll be seeing you

I had few familiar places, it seemed, to go back home to. There was very little that my heart embraced. No chestnut trees. No wishing wells. All that fueled me was anger and alienation.

My first on-ground recollection at Tan son Nhut was the smell. There was something ominous that just hung in the air. It reminded me of the odor of embalming fluid that lingers in the air of funeral homes.

My tour wasn’t especially dangerous, compared to what the Marines and Army were going through. About two or three times a month there would be a brief mortar attack. They’d usually last about thirty minutes or so and every thing would get back to normal.

It didn’t take me long to settle in. There was an on base beer hall adjacent to my barracks and I spent most of my off duty time there. Once I found it my life consisted of work, rotten chow, and about four hours a day of drinking.

Some of the other troops picked up on my surly attitude and tried to befriend me. The especially vulnerable of them, the Christians I met, got it full bore. They would usually start with the obligatory, “How you doin?”

“Alright, I guess, but I’d really prefer it if you’d leave me alone.”

“Why. I’m just askin’ because I care.”

“Sure.”

“People should care about each other. I mean, God cares.”

“Let’s not go there, alright.”

“What’s wrong with you, guy, don’t you believe in God?”

“No!”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Trust me, it’s true.”

“I don’t understand. I mean, look at all the beauty in this world. Where do you think it came from?”

“About the same place as all these mangled bodies we see every day.”

“I don’t understand how you can’t believe in God.”

“Well I don’t understand how you can, so we’re even. Now leave me alone.”

The conversations with Christians would almost all end that way. There was one exception, Paul Vartenisian. Paul was an NCO assigned to my duty section. He took an interest in me about six months into my tour. He seemed like a nice man to me and it seemed he really cared about me. The casual friendship went well until he came by the barracks one day. The conversation started innocently enough, then it got religious. “Phil,” he said. You’ve got to know God loves you. You really do.”

“Come on Sarge. Leave me alone.”

“He cares, Phil. He cares.”

“Sure.”

“You’ve got to know He loves you. He died on the cross for you.”

Those words – “died on the cross” – hit home, although I wouldn’t admit it. They brought me back to my childhood and the man who was being crucified on the fence outside my apartment window. “Just leave me alone. I want nothing to do with this.”

“I can’t, Phil, I can’t. Your life is worth everything to Him.”

“Get the hell outta’ here and leave me alone.”

Fred turned to go. “I’ll go, Phil, but I won’t leave you alone. I’ll be praying for you.”

“You just go right ahead for all the good it’ll do.” I said. “Your prayers mean nothing to me.”

In the six months or so I’d been in Vietnam I’d gotten used to sleeping with helicopters constantly flying over our barracks or the sound of bombs exploding in the distance. But, after the conversation with Sergeant Vartenisian things changed. I began to toss and turn throughout the night, replaying the conversation with him over and over in my head. It really bothered me but I couldn’t make sense of it. I would lay awake at night and wonder, “What are you so worried about. He isn’t praying to anyone or anything. Just go to sleep.” But, I couldn’t. The next time I saw Fred I took him aside and told him that while I respected his rank, I would kill him if he didn’t stop what he was doing. He never flinched. “Don’t you understand, Phil, God is trying to talk to you.” He said no more.

A week after that conversation I was assigned to take care of burning our section’s classified trash. It was very unpleasant duty. I took the five or six bags we had, grabbed an M-16, and went out to the incinerator, which was about a couple of hundred feet from our building. It was a very private spot on the top of a hill covered with tropical growth. I unlocked the gate, went in, and started to work. A couple of minutes into my ordeal I heard something rustling down the hill from me. I picked up the weapon and looked into the trees. Near the bottom of the hill I saw what appeared to be an old man. He was squatting down, defecating. “Something” seemed to possess me. A thought struck me. “Why don’t you shoot him? He’s just an old man. His life is probably miserable anyway. You’ll just be putting him out of his misery. Go ahead man. Do it!”

I raised the weapon and aimed down the hill. I was about ready to squeeze on the trigger when I heard these words, “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.” I stopped and wiped my face, which by now was sweating profusely. I raised the weapon again. And once more I heard the words, “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.” I knew the second time I heard them where they came from. These words that pleaded with me to stay my hand came from William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. They were Portia’s words to Shylock, pleading against exacting a pound of flesh, pleading for mercy:

“The quality of mercy is not strain'd,It droppeth as the gentle rain from heavenUpon the place beneath: it is twice blest;It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:'Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomesThe throned monarch better than his crown;His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,The attribute to awe and majesty,Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;But mercy is above this sceptred sway;It is enthroned in the hearts of kings,It is an attribute to God himself;And earthly power doth then show likest God'sWhen mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,Though justice be thy plea, consider this,That, in the course of justice, none of usShould see salvation: we do pray for mercy;And that same prayer doth teach us all to renderThe deeds of mercy.”

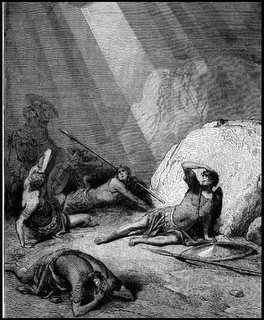

I dropped the weapon and fell on my face, sobbing. “I don’t even know if You’re real”, I cried. “But if you are please show me. Please, please, show me.”

I look back at that day now in wonder. There was nothing else in my frame of reference that would have prevented me from killing that old Vietnamese man that day than the words I heard. I was soon to learn that they did not come by chance, but that they had been spoken to me by the man in my dreams who was being crucified on the fence outside my window years before.

That incident, which could have been a tragedy, became the starting place in a journey of reconciliation I had walked away from in my youth.

I had few familiar places, it seemed, to go back home to. There was very little that my heart embraced. No chestnut trees. No wishing wells. All that fueled me was anger and alienation.

My first on-ground recollection at Tan son Nhut was the smell. There was something ominous that just hung in the air. It reminded me of the odor of embalming fluid that lingers in the air of funeral homes.

My tour wasn’t especially dangerous, compared to what the Marines and Army were going through. About two or three times a month there would be a brief mortar attack. They’d usually last about thirty minutes or so and every thing would get back to normal.

It didn’t take me long to settle in. There was an on base beer hall adjacent to my barracks and I spent most of my off duty time there. Once I found it my life consisted of work, rotten chow, and about four hours a day of drinking.

Some of the other troops picked up on my surly attitude and tried to befriend me. The especially vulnerable of them, the Christians I met, got it full bore. They would usually start with the obligatory, “How you doin?”

“Alright, I guess, but I’d really prefer it if you’d leave me alone.”

“Why. I’m just askin’ because I care.”

“Sure.”

“People should care about each other. I mean, God cares.”

“Let’s not go there, alright.”

“What’s wrong with you, guy, don’t you believe in God?”

“No!”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Trust me, it’s true.”

“I don’t understand. I mean, look at all the beauty in this world. Where do you think it came from?”

“About the same place as all these mangled bodies we see every day.”

“I don’t understand how you can’t believe in God.”

“Well I don’t understand how you can, so we’re even. Now leave me alone.”

The conversations with Christians would almost all end that way. There was one exception, Paul Vartenisian. Paul was an NCO assigned to my duty section. He took an interest in me about six months into my tour. He seemed like a nice man to me and it seemed he really cared about me. The casual friendship went well until he came by the barracks one day. The conversation started innocently enough, then it got religious. “Phil,” he said. You’ve got to know God loves you. You really do.”

“Come on Sarge. Leave me alone.”

“He cares, Phil. He cares.”

“Sure.”

“You’ve got to know He loves you. He died on the cross for you.”

Those words – “died on the cross” – hit home, although I wouldn’t admit it. They brought me back to my childhood and the man who was being crucified on the fence outside my apartment window. “Just leave me alone. I want nothing to do with this.”

“I can’t, Phil, I can’t. Your life is worth everything to Him.”

“Get the hell outta’ here and leave me alone.”

Fred turned to go. “I’ll go, Phil, but I won’t leave you alone. I’ll be praying for you.”

“You just go right ahead for all the good it’ll do.” I said. “Your prayers mean nothing to me.”

In the six months or so I’d been in Vietnam I’d gotten used to sleeping with helicopters constantly flying over our barracks or the sound of bombs exploding in the distance. But, after the conversation with Sergeant Vartenisian things changed. I began to toss and turn throughout the night, replaying the conversation with him over and over in my head. It really bothered me but I couldn’t make sense of it. I would lay awake at night and wonder, “What are you so worried about. He isn’t praying to anyone or anything. Just go to sleep.” But, I couldn’t. The next time I saw Fred I took him aside and told him that while I respected his rank, I would kill him if he didn’t stop what he was doing. He never flinched. “Don’t you understand, Phil, God is trying to talk to you.” He said no more.

A week after that conversation I was assigned to take care of burning our section’s classified trash. It was very unpleasant duty. I took the five or six bags we had, grabbed an M-16, and went out to the incinerator, which was about a couple of hundred feet from our building. It was a very private spot on the top of a hill covered with tropical growth. I unlocked the gate, went in, and started to work. A couple of minutes into my ordeal I heard something rustling down the hill from me. I picked up the weapon and looked into the trees. Near the bottom of the hill I saw what appeared to be an old man. He was squatting down, defecating. “Something” seemed to possess me. A thought struck me. “Why don’t you shoot him? He’s just an old man. His life is probably miserable anyway. You’ll just be putting him out of his misery. Go ahead man. Do it!”

I raised the weapon and aimed down the hill. I was about ready to squeeze on the trigger when I heard these words, “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.” I stopped and wiped my face, which by now was sweating profusely. I raised the weapon again. And once more I heard the words, “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.” I knew the second time I heard them where they came from. These words that pleaded with me to stay my hand came from William Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. They were Portia’s words to Shylock, pleading against exacting a pound of flesh, pleading for mercy:

“The quality of mercy is not strain'd,It droppeth as the gentle rain from heavenUpon the place beneath: it is twice blest;It blesseth him that gives and him that takes:'Tis mightiest in the mightiest: it becomesThe throned monarch better than his crown;His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,The attribute to awe and majesty,Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;But mercy is above this sceptred sway;It is enthroned in the hearts of kings,It is an attribute to God himself;And earthly power doth then show likest God'sWhen mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,Though justice be thy plea, consider this,That, in the course of justice, none of usShould see salvation: we do pray for mercy;And that same prayer doth teach us all to renderThe deeds of mercy.”

I dropped the weapon and fell on my face, sobbing. “I don’t even know if You’re real”, I cried. “But if you are please show me. Please, please, show me.”

I look back at that day now in wonder. There was nothing else in my frame of reference that would have prevented me from killing that old Vietnamese man that day than the words I heard. I was soon to learn that they did not come by chance, but that they had been spoken to me by the man in my dreams who was being crucified on the fence outside my window years before.

That incident, which could have been a tragedy, became the starting place in a journey of reconciliation I had walked away from in my youth.

There were trials to come before the reconciliation would be complete. I’ll cover that in part four, tomorrow.

1 comment:

Gripping stuff, Phil. I've read it before but it's worth reading many times.

Post a Comment